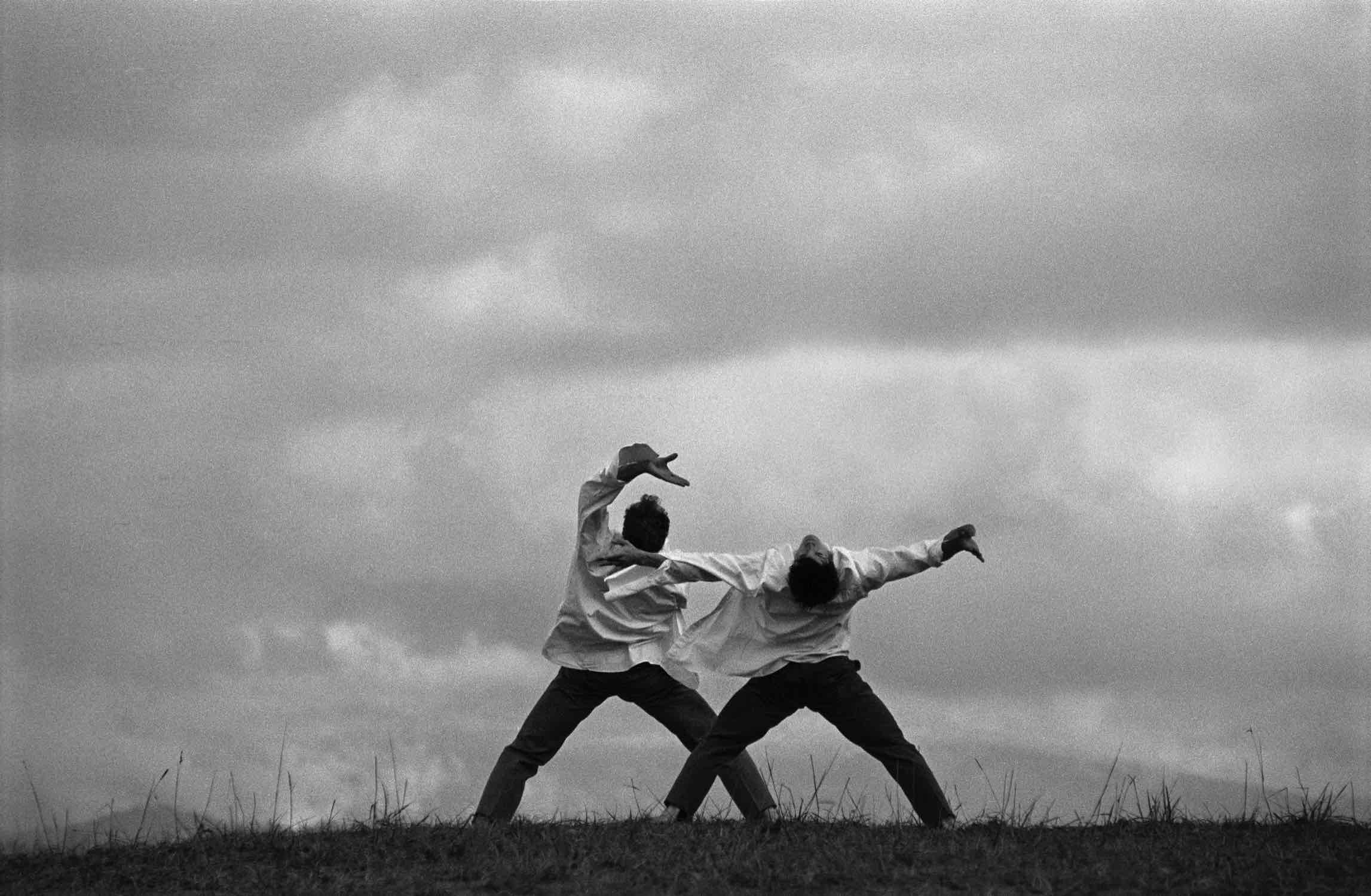

[storm]

(2006-2007)

Lee & McIntosh

A work for four performers. Dance, music, text, and interruptions.

Created by Lee Su- Feh and David McIntosh.

Performed by Aleister Murphy, David McIntosh, Ron Stewart, Yannick Matthon, and Lee Su-Feh.

Dramaturgy, DD Kugler.

Lighting, James Proudfoot.

Music, David McIntosh and Aleister Murphy.

Photos by Andrew Querner.

Lee Su-Feh's thoughts on [storm] and other things in an interview with Stephen White of Dance Victoria:

1. Briefly – what was the genesis of [storm]? What did you set out to explore with the piece?

When my son Junhong was born more than 8 years ago, one of the three women who oversaw the birth said to me, “The wonderful thing about having a boy is that you have an opportunity to bring up a good man.” Since then I have been wondering what it meant to bring up a good man. What the hell was a good man anyway? This, along with other things that intensify when one becomes a parent - thoughts about family history, immigration, war - these things came together as [storm]. I think of [storm] as a meditation on and hope for the future of my son through an examination into the past history of men, their fathers, their forefathers.

2. You are primarily a dance artist and your partner David is primarily a theatre artist/musician. How do you approach a work together – are you interested in a seamless integration of spoken word, music and movement or are you more interested in the tension that occurs between the forms of expression when they are put together in a larger piece?

I actually came into dance through theatre, having started my performing career in an experimental children’s theatre at the age of 16 in Malaysia. I decided to become an artist in an environment that exposed me to a great deal of spirited discourse about the relationship between ritual, folk, and classical practices within a post-colonial context. All these things continue to be huge influences in my practice as an artist. So, while I identify primarily as a dance artist, my view of dance has always included other disciplines, including theatre. David comes from a background of visual art/art video and punk/fuck bands. As an artist, I was and am attracted to David’s refusal to fit into easy categories. So the tension that occurs in battery opera’s work exists within our respective practices anyway. I think engagement between elements is always more interesting to me than seamless integration. It leaves things a bit more open-ended, and ultimately more open to change and transformation.

3. I’m still thinking about the integration of movement, text and music. Does a piece dictate its shape to you? Is there a time in your process when it becomes clear that the work requires some text in this section or a bit of movement there? Or conversely do you map a piece before you go into the studio to create the work.

The content dictates its form. The content comes out of the process in the studio and is informed by current obsessions and concerns. The process in the studio functions like an antenna, I would say, picking up all kinds of impulses, movement, sounds, thoughts, pictures which over time and with effort, get edited, distilled, framed into what is hopefully a coherent set of ideas. I don’t usually map out a piece before I go into the studio.

4. I know you like to take time – sometimes years as is the case with [storm] to work and rework a piece. What happened with the time you gave [storm]? What were the things that improved the piece?

Focusing on the men was probably the biggest thing. Originally there were two men and two women in Cyclops. The women in Cyclops were like the elements – wind, water – and mythical representations of these elements - the furies, sirens etc. After the premiere it became clear that these ideas would be present anyway, without the need to represent them with dancers. This stripping away of the mythical veneer provided a clearer framework for the piece and allowed the performers to become more human and vulnerable.

My approach to working with the body had also evolved over the time it took for Cyclops to transform into [storm]. I’ve now become less interested in form and more interested in principles and intention - how to articulate principles of movement and sensation in the body so that a score can be developed which allows the dancer the freedom to improvise and play to the full extent of their capacity, while still rigorously holding to the aesthetic and philosophical rules of the work. As a choreographer I have to become more alert to the dancers’ bodies - this makes the performers more alert and responsive to every moment of the performance, which makes the work itself more alert and which in turn, makes the audience more alert. I think. I hope.

5. Aside from an infusion of much needed new arts funding, if you could change the current system of artistic creation and dissemination what would you do?

Change is an ambitious word. Perhaps I’d like to remind people about the ways we can think about money in the creation and dissemination of art. We live in a commodity driven society and money is the means through which we interact socially; we can’t get away from it, but we can think about it differently. Currently we talk about the buying and selling of art, as if it is a commodity. But really, the art one makes is not for sale. It is an offering. Even if you buy a painting, you don’t own it. You are paying for the privilege of being in relationship with this painting in your living room, for example. And when one buys a ticket to see dance, you’re certainly not buying the dance because you can’t put it in your bag and take it home. You’re not even buying an experience. You go to the PNE and you have an experience. Did you buy it? No, you bought the corndog, the mini-donuts, the ride pass, the miracle shammy. But the experience is what you bring to all these things. So what are we buying when we pay $30 to see a show? I don’t know if we are buying anything. The $30 perhaps is a symbol of the contract between the artist and the audience that they are about to engage in an experience together. The funding that the artist receives is not the value of the art that is made but is the contract between the artist and the society where the society says yes, we value your place in this society and the artist says, yes, I agree to share my visions with you. I think. I hope.

6. How should an audience member prepare to see [storm]?

To take a moment to let go of the rest of their day, let go of expectations about what dance is, what theatre is, what narrative is. I think [storm] is a somewhat impressionistic piece. A bit like looking at those patterns that reveal a picture amidst the seemingly random pixels and dots and blobs. You kind of have to relax your eyeballs a bit before you can see the picture. So, have a drink.

When my son Junhong was born more than 8 years ago, one of the three women who oversaw the birth said to me, “The wonderful thing about having a boy is that you have an opportunity to bring up a good man.” Since then I have been wondering what it meant to bring up a good man. What the hell was a good man anyway? This, along with other things that intensify when one becomes a parent - thoughts about family history, immigration, war - these things came together as [storm]. I think of [storm] as a meditation on and hope for the future of my son through an examination into the past history of men, their fathers, their forefathers.

2. You are primarily a dance artist and your partner David is primarily a theatre artist/musician. How do you approach a work together – are you interested in a seamless integration of spoken word, music and movement or are you more interested in the tension that occurs between the forms of expression when they are put together in a larger piece?

I actually came into dance through theatre, having started my performing career in an experimental children’s theatre at the age of 16 in Malaysia. I decided to become an artist in an environment that exposed me to a great deal of spirited discourse about the relationship between ritual, folk, and classical practices within a post-colonial context. All these things continue to be huge influences in my practice as an artist. So, while I identify primarily as a dance artist, my view of dance has always included other disciplines, including theatre. David comes from a background of visual art/art video and punk/fuck bands. As an artist, I was and am attracted to David’s refusal to fit into easy categories. So the tension that occurs in battery opera’s work exists within our respective practices anyway. I think engagement between elements is always more interesting to me than seamless integration. It leaves things a bit more open-ended, and ultimately more open to change and transformation.

3. I’m still thinking about the integration of movement, text and music. Does a piece dictate its shape to you? Is there a time in your process when it becomes clear that the work requires some text in this section or a bit of movement there? Or conversely do you map a piece before you go into the studio to create the work.

The content dictates its form. The content comes out of the process in the studio and is informed by current obsessions and concerns. The process in the studio functions like an antenna, I would say, picking up all kinds of impulses, movement, sounds, thoughts, pictures which over time and with effort, get edited, distilled, framed into what is hopefully a coherent set of ideas. I don’t usually map out a piece before I go into the studio.

4. I know you like to take time – sometimes years as is the case with [storm] to work and rework a piece. What happened with the time you gave [storm]? What were the things that improved the piece?

Focusing on the men was probably the biggest thing. Originally there were two men and two women in Cyclops. The women in Cyclops were like the elements – wind, water – and mythical representations of these elements - the furies, sirens etc. After the premiere it became clear that these ideas would be present anyway, without the need to represent them with dancers. This stripping away of the mythical veneer provided a clearer framework for the piece and allowed the performers to become more human and vulnerable.

My approach to working with the body had also evolved over the time it took for Cyclops to transform into [storm]. I’ve now become less interested in form and more interested in principles and intention - how to articulate principles of movement and sensation in the body so that a score can be developed which allows the dancer the freedom to improvise and play to the full extent of their capacity, while still rigorously holding to the aesthetic and philosophical rules of the work. As a choreographer I have to become more alert to the dancers’ bodies - this makes the performers more alert and responsive to every moment of the performance, which makes the work itself more alert and which in turn, makes the audience more alert. I think. I hope.

5. Aside from an infusion of much needed new arts funding, if you could change the current system of artistic creation and dissemination what would you do?

Change is an ambitious word. Perhaps I’d like to remind people about the ways we can think about money in the creation and dissemination of art. We live in a commodity driven society and money is the means through which we interact socially; we can’t get away from it, but we can think about it differently. Currently we talk about the buying and selling of art, as if it is a commodity. But really, the art one makes is not for sale. It is an offering. Even if you buy a painting, you don’t own it. You are paying for the privilege of being in relationship with this painting in your living room, for example. And when one buys a ticket to see dance, you’re certainly not buying the dance because you can’t put it in your bag and take it home. You’re not even buying an experience. You go to the PNE and you have an experience. Did you buy it? No, you bought the corndog, the mini-donuts, the ride pass, the miracle shammy. But the experience is what you bring to all these things. So what are we buying when we pay $30 to see a show? I don’t know if we are buying anything. The $30 perhaps is a symbol of the contract between the artist and the audience that they are about to engage in an experience together. The funding that the artist receives is not the value of the art that is made but is the contract between the artist and the society where the society says yes, we value your place in this society and the artist says, yes, I agree to share my visions with you. I think. I hope.

6. How should an audience member prepare to see [storm]?

To take a moment to let go of the rest of their day, let go of expectations about what dance is, what theatre is, what narrative is. I think [storm] is a somewhat impressionistic piece. A bit like looking at those patterns that reveal a picture amidst the seemingly random pixels and dots and blobs. You kind of have to relax your eyeballs a bit before you can see the picture. So, have a drink.